¿Qué encontrarás en este artículo?

ToggleJ. F. A. de Soet

Heavy loses caused KLM Royal Dutch Airlines to introduce a major change in its organization structure. That brought to light a number of weaknesses, and placed added responsibility on managers at lower levels. Following an initial trial of management by objectives, a procedure was developed which has now become standard throughout KLM’s marketing management activities. J.F.A. de Soet, who is now the airline’s deputy president, outlines its approach, and provides examples of how it works in practice. These examples also provide a very good indication of the sort of results an organization can expect from a well-run MbO programme. Mr. de Soet admits that there have been some failures in the programme, but adds that these have provided some valuable lessons for the future. Overall, MbO has proved its value as an improver of management performance in marketing, and is now being extended to KLM’s other activities. The company’s objectives are clear. Now it is developing the managers to achieve them. ~W. J. Reddin

KLM Dutch Airlines is one of the major international airlines. To indicate the size and complexity of the company, it has 17,000 employees, about 30 percent non-Dutch, operating in about 70 countries. Sales activities include 280 offices, covering a route-network of 300,000 km. The operation is labour intensive; personnel costs account for about 40 percent of total operating expenses. In addition good communications are essential. And we are being faced with radical changes in technology, and an average annual growth rate of about 20 per cent.

With the pressure that became apparent to all airlines with the arrival of jets, a number of drastic changes were made. In particular, there was a major change in organization structure, and a considerable reduction in staff (from 19,000 to 14,000) at a time when the company was suffering heavy losses.

The KLM organization was restyled from a production-oriented organization to a market-oriented one. (We don’t fly airplanes, we fly passengers and cargo)

A number of weaknesses were revealed. The new organization structure placed increased responsibility on local managers, a responsibility which many were not fit to carry.

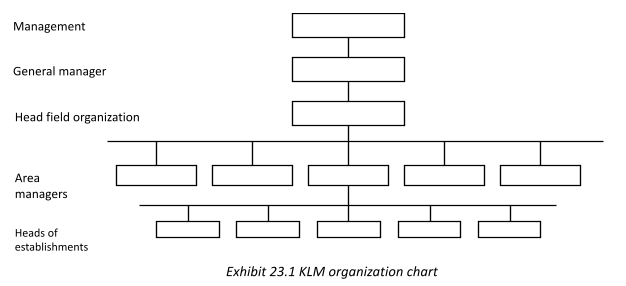

Outline of the organization structure

The main responsibility for commercial activities is delegated to a field organization, which is split up geographically. Area managers are responsible either for large single markets such as the USA, or for groups of smaller markets such as Central and South America. Each country or region has a manager and these managers have district managers where appropriate.

Reorganization meant that responsibility was placed at a lower level than before. Help had to be given to managers in carrying their new weight of responsibility. An initial analysis was made by outside management consultants. This analysis was carried out at various levels of the company by means of both interviews and a questionnaire. It led to the conclusion that manager training should be conducted in two ways: by formal two-week training courses in marketing and by local assistance in the field to improve management performance.

A prototype course was run and a pilot field operation was set in train. These two tests ensured that the follow-up action was aimed specifically at KLM’s requirements. Both prototypes were considered successful and became models for the programme that followed.

A number of courses were run by the consultants; they were followed by courses run by KLM’s own trainers to back up the field programme. For the field programme it was decided to take one establishment at a time. This formed a manageable unit for which one person, the manager, was responsible. While the consultants, the catalysts, were carrying through the programme, they were also training selected KLM employees in the principles and techniques. The procedure which has now become standard in the company is as follows:

- Establish the main purpose of the job

Investigate what the job is about and its real purpose is - Determine the vital result areas

What are the really important things the man is expected to achieve? - Set the standards of performance

What is the condition that exists when the task is being performed satisfactorily? - Establish means for measuring performance

Determine how actual performance can be measured against standards - Recommend ways to improve performance

List suggestions and/or requirements which would improve performance in the vital result areas.

To cover these steps, a form is used called a Job Results Guide which became a semi-permanent record of the procedure. Four of the main results illustrate how the programme works:

- A clear understanding between the manager and his boss of the purpose, priorities and objectives of the manager’s job

- Clear staff/line relationships

- Personal and unit performance standards

- Measurable results

Purpose, priorities and objectives

The first result was a clear understanding between manager and boss of the purpose, the priorities and the objectives of the manager’s job.

First example

Establishment managers were asked: What is the main purpose of your job? The answers in many instances were:

- to ensure the continuation or the extension of operating rights to and through the countries concerned

- to ensure that the organization runs smoothly (personnel matters, organizational matters, etc.)

However, after analysis and discussion between the establishment manager, the area manager and the “catalyst”, the main purpose was seen to be “to plan the level of sales turnover and resources required, and to achieve most effective deployment so as to obtain maximum return in line with company policy”, and the number one vital result area was to ensure that a 2-3 year plan showing expectations in sales and costs be submitted.

Second example

Priorities of the manager’s job were established and it was shown that time should be spent managing resources.

A given manager whose main tasks were general management and sales and sales supervision, had five sales representatives. The manager’s time was spent as follows:

General management 20 per cent

Own sales activities 60 per cent

Sales supervision 20 per cent

The manager’s capacity i.e., 100 per cent was 100,000 per year

Each of the salesmen produced 50,000 per year

Thus total sales were: 0.6 x 100,000 = 60,000

5 x 50,000 = 250,000

310,000

It was assumed that more time was needed for general management tasks (cost control, e.g. improvement needed) and that by increasing sales supervision from 20 per cent to 50 per cent the manager could increase the output per salesman by at least 20 per cent. The manager’s own sales activity therefore has to be reduced.

Thus the total sales would be: 0.2 x 100,000 = 20,000

(5 x 50,000) + 20 per cent = 250,000

320,000

The total picture was shown to have changed from:

20 per cent general management Cost Sales

60 per cent sales activity 60,0000 310,000

20 per cent supervision

Return = 5:1

to:

30 per cent general management Cost Sales

20 per cent sales activity 57,0000 320,000

50 per cent supervision

Return = 5.5:1

We are now developing methods and procedures to help plan the use of resources.

Clear staff/line relationships

The following two major problems in this respect were eliminated:

Staff Department managing line activities or taking over such activities, and

Staff Departments creating support material for the line, which was either not required or not coordinated with line objectives and activities (for example: leaflets, folders, tours, etc.).

First example

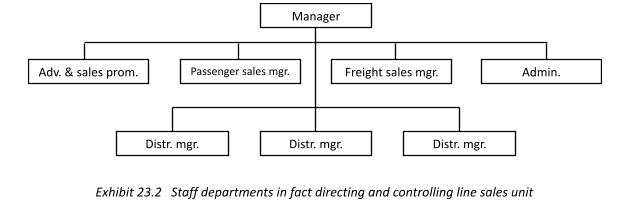

In some establishments the passenger sales manager and the freight sales manager, although in staff positions to the manager, were directing and controlling line sales units, which were officially supposed to be reporting directly to the manager (see Exhibit 23.2).

The result was that:

- Line sales units had to cope with three bosses (friction, inefficiencies).

- Passage and freight sales activities were badly coordinated (waste, inflexibility).

- Senior managers were not directly involved in and had virtually given up responsibility for marketing planning and the direction and control of field sales units.

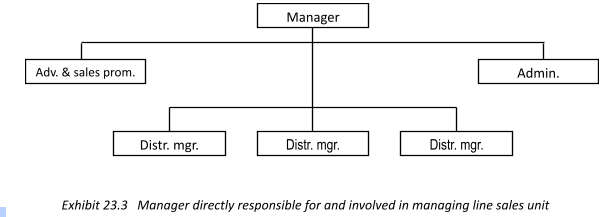

Analysis and discussions of the problem pointed the way to re-organization (Exhibit 23.3), in which

- Managers were made directly responsible for their main functions: the planning of marketing and the management of field sales units.

- Where product knowledge might be needed at the various levels and was found to be lacking, the manager and the sales unit managers were trained in matters and techniques of passage and freight marketing.

- Centralized activities, such as advertising and sales assistance, were carried out in a staff department responsible to the manager.

The results were:

- shorter communication lines

- a more direct involvement of establishment managers in their main line-tasks

- more expert knowledge at the levels where it was required

- a better selection of objectives

- simplified and more purposeful controls.

Second example

One establishment’s market research department thought up and carried out research projects on its own initiative or at the request of other staff departments, without checking the requirements of the line or gearing its projects to long –or short-term line objectives. This resulted in interesting, but often unnecessary reports not directed towards the line’s objectives.

A more penetrating analysis of Vital Results Areas meant that field managers were made aware of the assistance the market research department could give and were asked to submit their requirements with a preferred time planning. A market research department programme of projects could then be drawn up after selection and screening of the line department’s requests and after coordinating these with central marketing departments. A purposeful activity resulted which produced information required by the line. And resources could then be allocated to try and find more profitable markets.

Personal and unit performance standards

Areas of performance which were vital to the achievement of objectives, were not clearly defined and so the standards by which performance was judged were often haphazard and questionable.

This resulted in:

- a lack of confidence in the appraisal of individual performances

- a reluctance to accept responsibilities

- a reluctance to leave the proven paths

- a reluctance to delegate

- strict controls, which were directed at checking that activities had been carried out, rather than at judging the results

- achieved by such activities

- unit managers working in watertight compartments which made them competitors rather than constructive cooperators towards a common goal.

It was vital to the success of the programme that trust and openness should exist in all discussions. For this reason, it was clearly established from the start that consultants and catalysts were not there to criticize and report shortcomings, nor to attack the person, but to tackle the problem, to help in the search for clarification of purpose and improvement of total performance.

Although trust and openness were achieved, results were not the same everywhere because of differences in individual attitudes and character. Some managers found self-analysis easy and accepted a critical evaluation more readily than others. This response found its expression in standards, which led towards improved performances. (In many instances managers appeared to be eager to set their own standards of performance higher than the boss might have done for them). Standards were always set for a limited period; performance would be reviewed and new standards would be set after that period.

First example

Areas of performance were discussed with managers and with salesmen. Although they vary from area to area, and indeed from city to city, there has been concentration on tightening up sales methods. Obviously, one of the important areas of performance is the identification of opportunities where sales can be improved.

- Extra sales calls are directed to those addresses where an above average cost/revenue ratio may be expected.

- Each salesman pays at least four selected prospective visits a week. An annual average of 40 new accounts should be obtained.

- District manager works out a procedure to assess the salesmen’s performance and applies this procedure regularly.

But above all, the areas of planning and control have been found to be those in which good performance can influence results very quickly.

An example here is a salesman who should “suggest activities to support sales efforts with clients and/or agents in the next planning year, to be included in the draft marketing plan −these suggestions to be made on the basis of an accounts/agents survey” (planning). Furthermore, “reports covering activities are submitted weekly to the district manager” (control).

Second example

Standards included:

- For a unit manager: “To achieve profitability ratio of turnover to direct sales costs, in area X, of 12 to 1”.

- For a sales representative: “To produce X groups of at least Y passengers each, travelling transatlantic, for the period November to April (low season)”.

- For a freight sales manager: “To achieve an average income of at least X amount per kg in cargo sales for the periods June to September (high passenger-loads), September through December (cargo capacity problems)”.

Improvement in performance can take place only if results are measured. You don’t get what you expect, you only get what you inspect!

Measurable results

Wherever possible, standards of performance were expressed in objectively measurable units such as numbers or time. Often, however, one standard appeared insufficient to express the required performance level satisfactorily.

Sometimes, direct measurement of results related to a particular performance standard was not possible. In such cases, more than one measurable standard was used indicating the results of side effects of the performance under investigation. Where no measurement appeared to be possible, the usefulness of the activity was considered doubtful.

Standards thus always described the measurable conditions or situation existing when performance was considered good –when the job was well done. This made control relatively simple.

In reality, however, results in most establishments were measured against a predetermined plan (a budget), and in general did not relate to the resources utilized to achieve those results. Results were rarely measured against the market.

The need for all managers at this level to maximize the return on investment under their control with due regard to company policy requirements was discussed, and analysis of the existing control systems and their purpose was made. As a result, the following main guidelines for a basic control system were drawn up:

- Results should be measured in relation to market (market, shares)

- Results should be measured in relation to other results (passage versus cargo), district versus district, high season versus low season, agents versus direct sales, etc.)

- Results should be measured in relation to planned targets (targets per submarket, per season, per district, per geographical sales area, per destination, per line)

- Results should be measured in relation to resources utilized to achieve them. As a consequence, managers identified certain requirements and set out to:

- know the market potentials and development possibilities

- select the most profitable objectives

- seek out new fields for development

- see each cost item in relation to results to be achieved (targets)

- measure weaknesses and strengths in their subordinates

There have been a number of failures in this programme (personnal failures, misapplication of the principles). We have learned:

- Not to expect any results without the constant push and control from top management.

- To use consultants or catalysts. Their role is of great importance. They must be of high quality and maturity and trained in the latest techniques.

- To strive for participation. The programme has no lasting value at all if it is just imposed.

- Not to hurry the process. Attitudes cannot be changed overnight.

- Not to agree on performance standards for individual managers before the unit objectives have been set.

In general we found that management by objectives is a good way of improving the performance of managers and we are further extending it to other parts of the company at an appropriate pace.

We are involved in devising methods and procedures for marketing planning –so that new areas of performance can be identified. Managers with these tools can have a better understanding of how to select profitable objectives, and how to allocate marketing resources.

In all this, very little has been said about the basic problems of an airline. There are many. In spite of a turbulent time ahead future opportunities are promising. The whole world seems to be on the move at an exponential rate. We have to develop managers who accept the challenge of change.

“In the modern business in which knowledge is the central resource, a few people at the top cannot by themselves ensure success. The more business becomes a knowledge organization, the more executives there will be whose decisions have an impact on the whole business and its results.” ~Peter Drucker

That is why we are continuing with this programme. We believe our objectives are clear –we are developing managers to reach them.

Some lessons from our practical experience:

- In spite of all doubts and criticism, managing by and thinking in objectives has become part of the culture and infrastructure of KLM.

- The effect of MbO is directly correlated to the quality of the review and the guidance from the top.

- Review without action from the boss makes MbO a ritual dance.

- Integration of MbO in the company planning process (long/medium term) makes it a realistic tool for strategic management.

- An internal coordinator with adequate company experience and status is a must.

- To remain an effective tool MbO should evolve parallel to developments in the organization and culture of the company.

Postcript

KLM has developed MbO into an effective tool for strategic management

What happened after the MbO introduction in marketing management activities?

- MbO was introduced into the rest of the company with strong support from top management. MbO focused on senior management and, at a later stage, also on middle management.

- Later emphasis was on middle management, with a tendency to the “ritual”. Top management objectives (medium and

- longer term) were not always in the line with departmental objectives (yearly budget). The need to use MbO as a tool for strategic management emerged. This need was then realised –not without some friction.

- MbO is now integrated in the planning cycle.

- Younger senior managers also apply MbO to middle management.

- In coming years –we will be adapting our MbO procedures in order to make people more accountable, to get a better review of performance and to improve results:

This article was written after the successful introduction of MbO in Marketing Management. MbO has since become part of KLM’s culture.

The postscript reviews the developments since then. The message has not lost its significance for today’s management.

* Taken from: “Management by Objectives”, by W. J. Reddin, Chapter 23,

Published by Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited, India, 1988; pp. 225-232.