¿Qué encontrarás en este artículo?

ToggleWilliam J. Reddin

Life always gets harder toward the summit – the cold increases, responsibility increases.

~Friedrich Nietzche – The Antichrist Aphorism

No Utopia, nothing but bedlam, will automatically emerge from a regime of unbridled individualism, be it ever so rugged. ~Learned Hand

Once you have done your best to read a situation for what it truly contains, you broadly, have two choices. You either do a better job at adapting to the situation so that your managerial effectiveness increases −style flexibility− or you change the situation so that your managerial effectiveness increases −situational management. This chapter deals with the flexible response, the next chapter deals with situational management.

Most of both the psychological and management literature suggests that a manager with high flexibility is always likely to be a more effective manager. This is incorrect. Some managers change their minds and their behaviour to keep the peace. It might be perceived as being flexible but it is really drifting. Some situations require that a manager maintain a single appropriate style and virtually not vary it. One could hardly call this flexibility. It is clearly effective and we could call it resilience. Of course, maintaining a single style in a stuation that does not require that style will lead to less effectiveness and we could call that rigidity. We need to be crystal clear about these differences. To help us, we need a new term: this term is flex. This refers to changing managerial behaviour with no presumptions made about whether it is effective or not. Low flex and high flex behaviour are not more or less effective in themselves. Their effectiveness depends on the situation in which they are used.

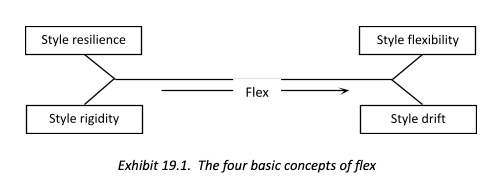

To build this line of thought into the 3-D theory, four basic concepts are used to describe both the range of a manager’s style behaviour and whether it is used appropriately.

- Style flexibility (appropriate high flex)

- Style drift (inappropriate high flex)

- Style resilience (appropriate low flex)

- Style rigidity (inappropriate low flex)

These four concepts can be represented as shown in Exhibit 19.1

The key dimensions shown in Exhibit 19.1 is flex. That is, changing one’s managerial behaviour. There are four possible outcomes of low and high flex as shown. These outcomes depend upon whether the high or low flex is appropriate to the situation.

So, while this chapter rather naturally espouses flexibility and links that to managerial effectiveness you must keep in mind that this is not true in every situation. Some situations may require the opposite. It is in those situations that low behaviour variation is used and situational management is used instead of style flexibility.

Flexibility and drift

If high flex managers are in a situation where their wide range of behaviour is appropriate, they are seen as having style flexibility. They are perceived as oriented to reality, sensitive, adaptive and open-minded.

Even with little ongoing change about them, managers sometimes find they need to have high flex in the apparently unchanging job they have. As a manager supervising 10 people you might easily find that two work best when left alone, two need continuous direction, three need to be motivated by objectives, and the three others need a supportive climate. So, in the space of a day you, as an effective manager may well use all four basic styles when dealing with such a variety as a dependent subordinate, an aggressive pair of coworkers, a secretary whose work has deteriorated, and a superior only interested in the immediate task at hand. Obviously, to try to use a single basic style in these situations would lead to low effectiveness to say the least. To the extent the organisation and technology allow individual treatment, high flex and sensitive managers could satisfy the demands of all these different situations and so achieve maximum effectiveness.

Many positions demand high flex because they require managers to deal with several different kinds of people or groups. The head of a voluntary agency could have to deal with a hostile or friendly boards, a tough central fund-raising organisation, professionals, volunteers, the press, the general public and immediate subordinates. If one viewed this position as a whole at one time the total flex demanded would be very high indeed.

High flex is likely to be demanded even more in the future. In many firms it is becoming commonplace, for younger managers, especially to undergo periodic changes in position with consequent demands for high flex. In addition, an ongoing organisation change can lead directly to departmental and job changes so that even in particular positions the situation changes. Rapidly changing technology and management techniques themselves produce further change. Sometimes the change is dramatic and sometimes gradual. No matter what the cause of the change, the rate of change is increasing and is imposing more strain on managers to learn new behaviour patterns and discard the old.

Whenever the topic of high flex is discussed, you may ask ‘Is high flex really role playing?’ The suggestion is made that role playing is not being yourself or that it is somehow manipulative. The use of high flex is the ability to play a large number of roles, or use several styles, which is the same thing. Such high flex is best seen as using various parts of yourself as appropriate.

If managers continually change their style and so use the same high flex in a situation where wide range of behaviour are inappropriate, they will be seen as having style drift. They are perceived as yielding, unpredictable, and perhaps too sensitive.

Resilience and rigidity

If as a low flex manager you are in a situation where your narrow range of behaviour is appropriate, you are seen as having style resilience. You are perceived as self-confident, orderly, stable and consistent. Style resilience is not a popular subject for many management educators. It clearly should be taught, however, and given a positive value. While there is conflicting evidence, some studies do appear to indicate that subordinates are more likely to be satisfied with any particular style as long as they know what it is. They are less satisfied when they perceive no particular consistent style. Predictability, resilience and subordinate satisfaction often go together. High flex managers succeeding low flex managers often find that their attempts to ‘loosen things up’ are not as rapidly successful as they had expected. Their subordinates’ expectations about how they should behave inhibit their introduction of managing with a higher flex.

Many situations demand qualities associated with resilience. Managers who want to be flexible about everything they do will not last long. The modern organisation is a recent and almost wondrous social institution. Its continuity and effectiveness, in part, is based on stability, predictability, and reliability. Its growth may, however, depend on quite different qualities. Obviously an appropriate mix of qualities associated with resilience and flexibility must be sought.

As a low flex manager you may find yourself in situations where a much wider range of behaviour is appropriate; you are then seen as having style rigidity. You will be perceived as having a closed mind, as intolerant and unsociable and as resisting change.

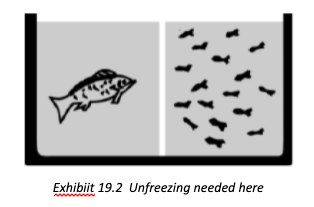

Much light can be thrown on the nature of resistance by referring to carefully controlled experiments. What follows may be seen by some as an extreme of unusual example. It is neither. It mirrors precisely what happens concerning resistance in organisations large and small. The experiment involves a fish tank almost filled with water with a glass partition in the center, a big fish on one side and small fishes on the other side.

In this experiment, then, the big fish is separated from its natural prey, the small fish, by a glass partition. It can see them but not get at them. What happens, quite routinely, is that the big fish attempts to get closer to the small fish but continually bumps into the glass partition. After doing this a few hundred times the fish gets rather sore and stops doing it. So far what has happened is fairly obvious. What happens next is not. The glass partition is removed, the small fish surround the big fish and the big fish makes no attempt to eat them. The big fish, in fact, dies of starvation in what is a sea of plenty. It has learned only too well that the small fish are unavailable and that if you try to reach them pain will result. It has difficulty in unlearning what it has already learned so well. The fish has been conditioned into not being able to learn or respond to a new situation. This experiment reflects precisely what is observed routinely in planned change programs.

Management thinks it is a good idea to ‘remove the glass’. This may be their wish to introduce a new climate or new methods in the organisation. Other managers in the organisation, most having been around for a long time with a different system, have learned only too well to ‘not go after the smaller fish’. Top management may initiate training courses, wave flags or give speeches all concerning the fact that they have removed the glass but the middle managers simply do not believe it and do not respond. Their problem is that they have some unlearning to do because the prior learning was so good. Not learning but unlearning. In short, they need unfreezing. They need to see what is really in their current changed situation rather than what used to be there.

Several times, I have been in a situation where I was quite convinced, and later proved correct, that the top team had made many changes and intended to make many more and would carry them through. When meeting with those who reported to the top team I find that, in the first year or so at least, they do not believe a word of it. One consequence of this is that planned change programs need maintained effort and a substantial amount of work on unfreezing and getting managers to face and accept the new reality.

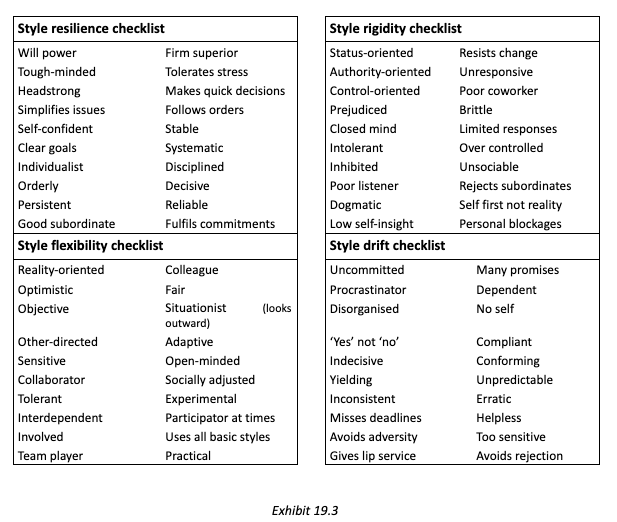

Four checklists

These four checklists will help you gain an understanding of four concepts, style flexibility, style drift, style resilience and style rigidity. You might look at the four lists and check off the words you think apply to you and reflect some things you might want to try and change in yourself.

Are you a naturally flexible manager?

There is little question that some managers are naturally more flexible than others and this is related, to a degree, to their personality. It is also true that increased flexibility is easily learned. Four personality characteristics underlie high flex behaviour. You might consider yourself on each one of them.

- High ambiguity tolerance (comfortable in unstructured situations)

- Unconcern with power (not control oriented)

- Open-belief system (few fixed ideas)

- Other-directed (interested in others)

High ambiguity tolerance (comfortable in unstructured situations)

High flex types have a high tolerance for ambiguity. They are comfortable in an unstructured situation where one or more of the past, present or future are ill-defined. They are not too threatened by rapid, unexpected changes. Not ones for paperwork, they see this an unnecessarily structuring a situation best kept loose. They favour short reports, loose ground rules and open-ended planning and scheduling. It is important to them to maintain a friendly, easy atmosphere where the ‘old boy’ approach is used more than ‘standard operating procedures’. Approaches that could be characterised as ‘right or wrong’, ‘black or white’, ‘go-no-go’, and ‘win-lose’ are foreign to high flex managers.

Unconcern with power (not control oriented)

High flex managers will often listen more to subordinates than to superiors because they are unconcerned with power. They generally favour flattening the status and power differences between levels and usually avoid displays of status symbols. They are in favour of most forms of participation. High flex managers are sensitive to the way things are. They see good management as the art of the possible. They would prefer to have things develop and flow naturally rather than go one step at a time or be dramatically restructured.

Open-belief system (few fixed ideas)

High flex managers are open-minded. They are ready to see new points of view and to expose themselves to influence. They could easily hold a particular view on one day and change their minds, in the light of new evidence, a day later. They are more concerned with full knowledge than in having their prior beliefs confirmed. They are less likely than others to take extreme positions for or against anything. They have a capacity to accommodate a wide range of view-points and do not feel they must make a successful synthesis of them.

Even when unable to accept another point of view, they will always listen to it, usually contemplate it seriously and often live comfortably with it, although it may be contradictory to their existing belief system. They are usually open to new inputs from any source. They are on a continuing search for maximum contact with their environment and are thus open to influence. This openness leads them to drop prior methods with ease. Not tending to hold extreme, fixed views, they argue less vehemently than others. They are tolerant of others holding opposite views. If they have to change their minds, they can do so easily. They are, therefore, as much interested in hearing other views as in pushing their own.

To have high flex, managers must have few intrusive personal needs. They must not have a need to do things in one way, to have a particular relationship with others, to live according to a particular ideology or to accomplish a particular thing.

Other-directed (Interested in others)

Their openness to influence and their unconcern with power, make the high flex type a team member. They want to be involved in analysis, planning and decision making with others. They seek collaboration with their coworkers and are willing to accommodate a group view rather than maintain their own. They thus are usually more prepared to work for a consensus decision than for a vote. They look for that creative solution or synthesis that everyone will accept. In fact, they find it a challenge to work for such a solution which combines all views, even though the final decision may have some ambiguous elements.

High flex managers tend to get involved with people as individuals, not just as subordinates or coworkers. They do not see others as bounded by their role. They are sensitive to individual differences and want to respond to them. They sometimes find themselves involved with another manager’s home problems. They do this not because they are inquisitive or have high relationship orientation but because they are interested in a variety of inputs and thus look at the total person rather than at a human frame bounded by a job description.

Both high flex and low flex types can be seen as fair to others but for different reasons. High flex types are fair owing to their willingness to consider all points of view.

Low flex types are fair because they want to treat everyone equally and because they want to lower the ambiguity of the situation. The high flex type is generally more concerned with fairness to the individual, the low flex type with fairness to a particular social system as a whole. The high flex type tends to be sensitive to the relationships orientation elements in a situation. The low flex type to the task orientation elements.

High flex demands

Some managerial positions make high demands on flex so that a variety of basic styles must be used to produce effectiveness.

Creative directors of advertising agencies have to deal with a creative staff, the agency management and account executives. With a creative staff, they must provide a supportive climate; with the account executives, they must act like sales staff and push for their ideas; with the management, they are expected to take a rational, hard-headed approach with costs, profits, planning and running a department. Small wonder that low flex, creative directors are thought to be excitable and tend to develop ulcers rapidly.

Job characteristics which usually demand high flex include:

- high level management

- loose procedures

- unstructured tasks

- non-routine decision making

- rapid environmental change

- manager without complete power

- many interdependent coworkers

Very few jobs possess all the above-mentioned characteristics, but the following positions, having one or more of them, tend to make higher than average demands on flex:

- senior manager

- personnel manager

- service-function coordinator

- research administrator

- manager of staff department

- supervisor

- university CEO

The more senior the manager, the more important high flex is likely to be. No administrative problem repeats self in every detail. The higher the level, the more complex successive problems are likely to be. In many policy issues, the personality of the shaper has an enormous influence. It is then that flex can be of the utmost importance. Senior executives are continually encountering exceptional circumstances which fall outside established patterns of solutions. It is how they handle these situations that most determines their overall effectiveness.

High flex managers in a low flex organisation may not be allowed to manage effectively, and if they do, they could get fired.

The general manager of a 500-employee plant was what everyone would call a ‘great guy’ –except the Chief Executive Officer, who was the general manager’s immediate superior. The CEO was a bureaucrat and wanted the general manager to pay more attention to detail, stay within budget, make sure sales staff sent in reports weekly and stay close to the telephone. At one point there was serious consideration given to firing the general manager even though by any standard of managerial effectiveness an outstanding performance was demonstrated by the doubling of profits in three years and by far outstripping the head office projections of both sales and profits. The general manager ultimately left and was able to immediately obtain double salary in a new job.

As a flexible manager you are perceived as having few personal needs or biases which might lead you to interpret wrongly the real world. You are reality-oriented, and this reality guides your action.

You are not led to analyse a situation in terms of how you think things should be. Rather you read a situation for what it is and for what can reasonably be accomplished. You seldom identify with lost causes but more often with objectives being achieved. As a flexible manager you are essentially an optimist about yourself and about the situation. Often you see things you do not care for but know that with time and appropriate behaviour, the situation can be changed.

As a flexible manager you recognise that you live in a complex world, you are aware that a wide range of responses are necessary in order to be effective in it. You are very sensitive to other people and are not only sensitive to their differences but accept the differences as normal, appropriate and even necessary. You are trusted and believe that your proposals for change are based on improving overall effectiveness and are not intended simply to satisfy your own needs in some way.

As a flexible manager you spend more time in making decisions and less time in implementing them. You are concerned with method of introduction, timing, rate of introduction and probable responses and resistances. In spending more time on deciding how to implement decisions, the implementation period is shortened considerably. You seldom make snap decisions. As a flexible manager you use team management when appropriate. This gives you an ideal opportunity to use your flexibility.

You are likely to be willing to experiment with changes that have only a moderate chance of success. You know the world is complex and recognise that any change may bring unanticipated consequences so you are prepared to test a large number of ideas.

You are willing to accept a variety of styles of management, varying degrees of participation and an assortment of control techniques. Appropriateness is your only test.

In the course of a few hours, you have used a variety of basic styles as a flexible manager. You adapt your style to what is then demanded. You use participation at times, and at other times you do not.

Why you may resist becoming more flexible

Quite apart from your personal defences there are many other explanations of why you may resist change in yourself.

Why resistance occurs

- No direction to change

- No skills to change

- No pressure to change

- Known is safer

- Personal effectiveness

- Shell shock

- Prior learning

No direction to change

Resistance to change often arises simply because the type of change desired is not specified clearly enough. It helps to ask, implore or demand others to change if you are not clear on the exact nature of the changed behaviour required. Often, the unwritten desired direction is “Change to whatever I want at the time.” In some settings this might be useful but in normal settings it is not common and normally less effective. As an example, the change request to improve communication’ contains really no information on direction of change. Does this mean more talk, less talk, more memos, less memos, communication upwards, communication downwards, communication laterally, listening, more speed reading courses needed, more speed writing courses needed, more basic language courses needs, more use of the telephones, less use of the telephone, longer meetings, shorter meeting. Surely the point is made.

Other examples of quite useless direction for change concern such statements as “Let’s make the organisation more participative or more 9.9 Theory Y.” These statements contain no useful information. All this is why planed change must start with the notion of plannec change objectives and how to measure these objectives. The whole point being to give change direction a high degree of specificity. Without this planned change must stop dead in its tracks because everyone does not agree on what changes are being considered.

No skills to change

Change sometimes fails because managers are not provided with the skills needed to implement the change. Perhaps the new corporate planning scheme requires that managers have an increased ability to make a plan. It may well be desirable to arrange that every manager has a one or two-day course on planning which might include such things as being competent at Critical Path Analysis or Programme Evaluation Review Technique or some other technique. Performance appraisal schemes often fail because they are introduced simply as a form which is distributed and managers told, essentially “To get on with it”, rather than being formally exposed to a one day course, probably using video tape feedback, which enable them to practice their use of the form and all that it entails on strangers before they use it with their subordinates.

If one needs to make an organisation more participative it might well be a good idea to offer managers a short one or two-day course in listening skills or in participative meeting skills. Again, to give them an opportunity to learn in a neutral and safe environment before they apply it on the job.

No pressure to change

In addition to directionality and skill level the successful implementation of change requires some pressure of some kind. In its starkest terms it might be financial rewards for successful behaviour change and financial punishments for no behaviour change. More common, the pressure arises from a clear message from management that they want the change and are quite determined to see it implemented. Other pressures for change may be created by talks, meetings and system changes. The single best pressure always is that top management is seen to be supportive of the change and, as it applies, to be directly engaging the change itself.

Known is safer

It is quite common for an effective manager to resist change. The effective manager resists change because of the danger that in making a change the present good level of effectiveness might be decreased. In fact, the simple truth is that change introduction often results in a short term decrease in performance while new skills are being learned or while errors in introducing the change are being weeded out. Think of your own situation and some skill which you acquired too late. Perhaps you waited too long to become computer familiar. You thought that the time taken to learn it would lower your effectiveness with other things. Perhaps you took too long to become really able with a dictating machine. You were concerned that the time taken to learn it would detract from effectiveness. It is important to understand that a manager who is effective and who resists change may be doing so simply because of fear of lowering the good standard of performance at the moment.

Personal effectiveness

While the approach so far has taken a fairly understanding view towards resistance, it can of course arise from purely selfish motives. If one is primarily interested in personal effectiveness, that is meeting one’s own personal rather than organisation objectives, one may well show high resistance to proposed changes. If one is overly concerned with one’s own position, power, possible career route, size of office, work arrangements, numbers supervised and a host of other things; and puts these first, then it would be natural to expect a higher resistance to reasonable changes which would improve organisation rather than personal effectiveness. The best way to deal with this issue is to raise it with one’s colleagues. The question that comes naturally is “Are you objecting to this change because of managerial effectiveness or personal effectiveness reasons?” This is a routine question in organisations with good team work and candour.

Shell shock

Shell shock, in military medicine, applies to a psychological malfunction wherein the individual cannot cope with the existing unthreatening reality because of lingering feelings about an earlier shocking reality which was impossible to handle. Things are not quite that bad with most organisations, but they sometimes occur; otherwise, why would people involved in change frequently have heart attacks, ulcers, or become alcoholics? All of these can be seen as aspects of shell shock. Some companies pride themselves on being abreast of every new idea in management. This obviously can be healthy, it depends to what extent it is carried. But, if in an organisation one year it is job enrichment, the next year quality control circles, the next year management by objectives, the next year participative management… and so on one could reasonably expect that the amount of change would be so great that it would be impossible for most managers to deal with it, and more important, integrate its variety into some sense. Surely, this is an understandable reaction. Planned change should involve a single comprehensive set of ideas over a period of time long enough for them to be integrated into the ongoing life of the organisation.

Prior learning

This refers back to the fish experiment. Some people cannot change because they have learned the wrong things too well. This is sometimes called trained incapacity. It is the most important example of the need for unfreezing.

Will you increase your flexibility?

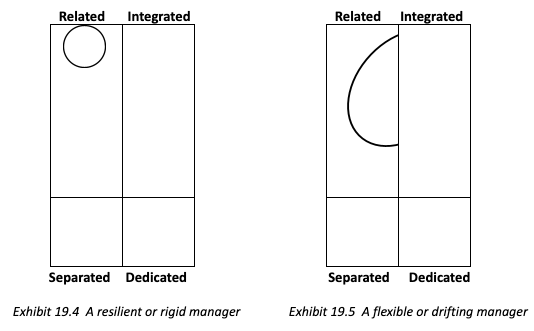

You can think about your flexibility in terms of the basic styles. Is your behaviour range so narrow, as represented in Exhibit 19.4, that you are in one corner or in one of the others. Or do you have a broader behaviour range, as presented in Exhibit 19.5 with some capacity to use at least three of the basic styles?

From Exhibit 19.5 alone we cannot say whether the manager is more or less effective. We do know the manager has the capacity to use three styles. If one or more of those styles is effective in a situation then we would use the label flexibility, and if not, we would use the label drift.

Think about your results on the style test. If you had a double dominant basic style, such as missionary and developer, it is possible that your style variation is limited more or less to related. If you have a fairly flat profile it is probable that your style variation is fairly wide.

Think for a moment about the capacity for your own behaviour change. A rich relative has died and in the will has left you an iron foundry. There is one key proviso. You must personally go and manage the iron foundry and if you change its current one per cent return on investment to five per cent return on investment within a four year period then the iron foundry becomes yours and you can do with it whatever you will. The estimated value with that kind of turnaround would be several times more than your expected income for the rest of your life. Do you think that you would be sufficiently motivated to attempt to improve the organisation effectiveness of the iron foundry? While you probably have had no experience in this line of work do you think you might in fact have a good go at it and you might be reasonably effective if you put effort into it? Most people, like yourself, would say something equivalent to “I will give it a go”. Suppose, instead, you were asked to lead a university department of management. You were told that in the department there are lecturers all of whom are technical specialists in narrow subjects such as finance, tax, accounting, human relations, organisation behaviour and statistics. You were told that they set their own curricula, they set their own examinations, they decide alone which students pass and which ones do not, it is not at all customary for heads of department to ever view a faculty member teaching; in short, you have little control. You are asked to improve the general organisation effectiveness of the department and to represent the department well to the community. Do you think that this might b an interesting job for five years? Do you think that if you thought it was interesting you might try it?

The point with these two examples is that they would require completely opposite kinds of behaviour. The first would require a heavily dedicated task oriented behaviour and the second should require a highly related type of behaviour. You, in fact, believe that you would do either job if needed. One must conclude that you believe that you have a wide range of possible behaviour.

It is not the capacity for behaviour change that is the limiting factor –it is the clarity of perception that makes it obvious that a particular change to a type of behaviour is needed. We all have an innate wide range of potential behaviour. We and other must learn to use it. We have no room for the resisting ones who claim that behaviour is difficult to change or cannot change.

Some claim that change in behaviour is a form of manipulation and that it confuses others. If the behaviour change is for personal effectiveness reasons so that you can serve your own needs then it is appropriately called manipulation. If the behaviour change is to serve situation needs and to improve managerial effectiveness then obviously it is style flexibility. Most people are quite able to sort out one from the other.

To help maintain their own resistance some argue that the expectation of behaviour change is not reasonable as you cannot change personality. It is in fact difficult to change personality, if not impossible. It is easy however for us to change behaviour. We are changing our behaviour conytinually. We act differently with different subordinates, we act differently at home, we sometimes treat our individual children differently, we act differently with our sports team and with our friends. Behaviour changes all the time. It is natural.

There is no need to be pessimistic about changing your flexibility. The simple fact is that several excellent methods exist to overcome resistance. What is probably the most advanced method is a behavioural science type event called the 3-D Managerial Effectiveness Seminar as described in chapter 22. It has these nine main components:

How to improve flexibility

- Theory: about behaviour

about situation

about effectiveness - Awareness: own behaviour

own situation

own effectiveness - Skills: situational sensitivity

situation management

style flexibility

To help managers change they need some cognitive framework. They need what is, in effect, a common sensible easily understandable language so they are all talking about the same thing in the same way. This language is obviously based around behaviour, around situation and around effectiveness. The behaviour may well consist of managerial styles, the situation or various situation elements such as technology and superior style which affects one’s own behaviour and effectiveness. A very clear statement must be given about effectiveness itself. That is, what it is, how it is measured and how it should be improved. Another part of helping people to improve their flexibility should be an enhanced awareness of their own behaviour, their own situation and their own effectiveness. This, in fact, applies the theoretical knowledge to their own situation. The whole of this is to overcome distortion.

These seminars start with a simple statement “The objective of this seminar is to help make you become more objective about your situation”. This may seem a strange way to start a seminar on managerial effectiveness but it is the best way if you follow the ideas here. Obviously, the final segment of the event must be skill improvement. What are the three skills of an effective manager? They must be the ability to size up situations for what they really contain, situational sensitivity; to change situations that need to be changed, situation management; and the ability to adapt to a situation which cannot or should not be changed, style flexibility. All this leads, logically, to improved managerial effectiveness.

What does becoming more flexible mean – really?

What is behaviour change really? Some, as a defence, imagine it is something to do with changing one’s basic beliefs, changing one’s lifestyle, moving from one role to another in terms of styles and other dramatic expressions. Effective behaviour change may involve one or more of these managerial effectivenss with a relatively small amount of behaviour change which too many will be invisible. Here are some ideas:

What is behaviour change?

- More or less planning

- More or less talking or memos

- More or fewer risks

- More or less consideration

- More or less participation

- More or less use of a style

- Higher candor

Remove your desk

Some of the items on this list will seem to be quite minor but can be quite important. Some managers are the opposite and like densely prepared bureaucratic schedules for everything even when they are not needed and do not lead to improved effectiveness. Perhaps you should talk more or less or use memos more or less. Think about what you are doing now and really whether that you are doing is the most effective method. You cannot possibly address this issue until you know what your ‘outputs’ should be and, to a degree, whether you are achieving them.

Are you taking enough risks, or are you taking too many? One sever hindrance to behaviour change is the unwillingness to take any risks at all. Change of necessity involves risk taking. It is simply because we have not been there before. One must expect a short term decrement of performance with virtually any behaviour change. Perhaps you are showing too much consideration to others, perhaps too little. Perhaps you are using too much participation or perhaps too little. Think of the styles you use. Could you use some of them a bit more or a bit less? Should you be more candid about performance?

The point of all this is to indicate that important behaviour change to improve managerial effectiveness need not be dramatic. Overcoming resistance in one’s self and in others is not necessarily high drama. It can often be things that are virtually invisible to the casual observer. There is no reason why we should not engage such behaviour change and no reason why we should not expect others to as well.

We need to understand resistance always but we need not accept it always.

Taken from the book: “How to make your management style more effective”,

by W. J. Reddin, Section D , Chapter 18,

Published by Malaysian Institute of Management, Malaysia, 1990; pp. 166-181.