¿Qué encontrarás en este artículo?

ToggleWilliam J. Reddin

To be great, to be a person of stature, a man must have character, judgment, high intelligence, a special aptitude for seeing his problems whole and true –for seeing things as they are, without exaggeration or emotion. ~Field Marshal Montgomery

How can we avoid the two extremes; too great bossism in giving orders, and practically no orders given? … My solution is to depersonalize the giving of orders, to unite all concerned in a study of the situation, to discover the law of the situation and obey that. ~Mary Parker Follett

Your situational sensitivity is your skill in reading a situation for what it really contains. Obviously, a key managerial skill is the ability to size up a situation. A manager with the sensitivity to read a situation for what it actually contains, and the sensitivity to know what behaviour would actually constitute effectiveness in it, is more likely to be effective.

Age and experience do tend to improve situational sensitivity as this skill is a component of experience. However young managers sometimes show a brilliant understanding of situations and of what must be done to produce effectiveness. They know when to push hard, when not to, whom to see and the appropriate timing. Sensitive managers will know what resistances stand in the way of being effective and what they can overcome and must overcome to be effective. Although situational sensitivity is seldom perfect, managers can learn ways to improve it.

Sensitivity requires alertness and curiosity. Sensitive managers fit scraps of information and hunches together. Like any scientist, they look at details to construct the whole. From a fire bed and an arrowhead, an anthropologist constructs a civilisation. From the way in which a policy is received by different divisions sensitive managers can construct the reality of power politics in an organisation.

If a manager makes a series of interventions in situations which later prove effective, then it is highly probable the manager has a high sensitivity to situations. If not, the manager would have made the wrong moves. If, however, a manager does nothing, this alone does not indicate whether or not there is high or low sensitivity. One may know what is wrong but not know how to do anything about it.

Situational sensitivity is a diagnostic skill not an action skill. This simply means that a manager may score high on situational sensitivity and yet do nothing with the skill. The well-trained psychologist, sociologist, or anthropologist may have the highest possible situational sensitivity yet the lowest possible effectiveness as a manager. To be effective, the sensitivity must be matched with one but preferably both –style flexibility and situational management.

Management training exercises are available which measure situational sensitivity with great precision. They consist of depicting a situation by a film or written case study and then asking the manager to make a series of observations concerning it.

Situational sensitivity is a particularly useful skill when dealing with other departments. As often occurs in such situations, managers have no real power. They must elicit co-operation based on mutual understanding. They are more likely to be effective if they pay some attention to the realities and the fantasies of how each department operates, who the key people are, where the power really lies. While useful, sensitivity is not such a crucial skill in stable or highly structured environments. When a manager is trained for years for a particular kind of situation which is unchanging, the need for sensitivity decreases. In some such situations it may even be a hindrance because the manager may be acutely aware of what is needed yet be unable to do anything about it.

Do not trust to luck

Many highly sensitive managers, politicians or for that matter entrepreneurs are often described as lucky. The term ‘luck’, like magic, is really a device simply to explain what is to some an otherwise inexplicable outcome. Luck seldom explains managerial effectiveness. The manager in the right place at the right time with the appropriate resources did not come there solely by chance, although it may appear that way. They very often understood the existing or potential situation and were prepared for the opportunities as they came.

Managers with low sensitivity tend to have more difficulty than others in learning theories such as the 3-D Theory of Managerial Effectiveness. The far 3-D Theory was designed to be reasonably free pff bias and of any particular ideology save managerial effectiveness. Unlike many theories it does not suggest that flexibility, resilience or relationships are always good. It operates this way, in part, through the use of tight definitions and a situational approach. Some managers have difficulty in learning 3-D because they cannot see the difference between one situation and another. Without some skill at this level, it is impossible to understand the usefulness of 3-D, let alone have the skill to use it.

The causes of low situational sensitivity

While it may seem surprising to you the main reason why you, or any manager, may have lower situational sensitivity than might be desirable is lack of knowledge about self. That is, low style awareness. If you distort your self to yourself, that is, do not know where you stand or where you really are, you will automatically distort the situation as well. The first step then to improving situational sensitivity is to improve style awareness. Style awareness is the degree to which you appraise your own style correctly. It is knowledge of your impact on others, not of your impact on yourself. The prime usefulness of this self-knowledge is to enable you to make a more effective impact on the situation, not so you can marvel at your own psychic interior. Effective managers must know the impact they are having on others. Without this knowledge, they cannot assess the situation they are in and cannot predict the results of their own behaviour. Many types of group-dynamic management training courses attempt to, and usually can, improve style awareness, as can marriage or even children.

Hate at first sight

One indicator of low situational sensitivity is having a tendency to take an instinctive dislike to some people. There are many rather natural and obvious reasons why this might occur but some people make a habit of it. Why might you take an instinctive dislike to someone, perhaps a new work colleague, you have never really known. There are three main reasons for this kind of irrational response. It might be that the person reminds you of someone you dislike, or displays a quality which you dislike in yourself or the new person is in some way a threat to your security. This threat to your security may be anything from making higher performance demands on you, showing you up at work in some way just by simply being more effective, or bringing in some pressure for you to change your comfortable work habits.

The fatal flaw

All of us have flaws; a few of us have fatal flaws which we seem condemned to keep repeating in different contexts. The flaw is best identified by looking at the situations which most often lead to more trouble than they should. The situation may involve a superior when the manager is in a low power situation, it may involve a coworker or a subordinate. It may involve planning, organising, or controlling. It may be confronting disagreement, making a difficult decision, usually its postponement, trying to satisfy everyone, over-reacting to criticism, being vague about poor performance or any one of many more. Fatal flaws often come disguised. The same basic flaw may have occurred in a dozen different ways. Only if a flaw is recognised, can it be managed. It can only be managed by the person whose flaw it is.

Situational sensitivity alone

Situational sensitivity alone is of little value to the practising manager. If a manager cannot use the knowledge, then a manager may as well not know it. Those who go through life as hostile or as friendly observers of the scene, are serving some need to appear intellectual rather than to be useful and, therefore, to be effective. One does not like to feel one is being analysed, and this is what situational sensitivity alone can lead to. Sensitivity must be related to an action programme of either managerial flexibility or situational management. Some managers have high sensitivity but low flexibility. They usually tend to change situations rather than change themselves. They use situational management.

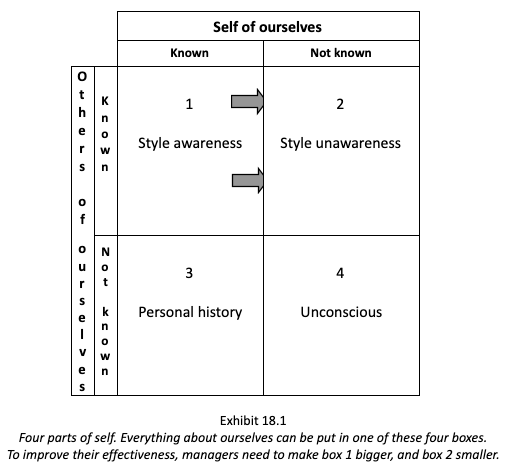

Four parts of self

Everything known and not known about ourselves can be put under one of four headings

- What we know and others know –style awareness. (This is everyone’s business)

- What others know and we do not know –style unawareness. (We must make this our business)

- What we know and others do not know –personal history. (This is our business only)

- What we and others do not know –unconscious. (This is no one’s business)

These can be arranged as demonstrated in exhibit 18.1. The idea on which this exhibit is based (only terminology is changed) was developed by two psychologists, Joe Luft and Harry Ingham. They call it the Johari Window. See why?

This exhibit sharpens the importance of decreasing our degree of style unawareness. The style unawareness area is that part of our behaviour which others are well aware of but we are not. In simple terms, we may be acting in ways toward others, perhaps rejecting them, of which we are essentially unaware. Clearly to be effective with others, we must know just what kind of impact we are making. To become more effective then, a manager needs to make window 2 smaller by increasing the size of window 1.

Without a reasonable degree of style awareness, it is difficult to use management style concepts. Without knowing our own basic style, it is all too easy to distort the style of another or the basic-style demands of a situation itself.

As a result of training, managers often experience a marked style-awareness shift. They see their style behaviour in a markedly different way. As part of pre-work for the 3-D Managerial Effectiveness Seminar, managers complete three different managerial inventories which reveal how they see different aspects of their style. A total of 240 points is distributed over the eight managerial styles or 80 on each inventory. On the last day of the seminar, the inventories are again completed according to how the managers now see their typical style behaviour as it existed before the seminar. A record is made of the amount of points shifted from one style to another. The maximum shift is 480 points. A shift of 0 points would indicate no change in style awareness. On almost every seminar, some managers shift over 250 or even 300 points indicating a marked change in style awareness. The average shift is about 140 points.

Some questions for managers to ask themselves

Style awareness is difficult to improve by simply thinking about it, but some assistance may be obtained by answering each of the following questions honestly:

- If someone said of you “You sometimes act like a kid”, what behaviour would they be thinking of?

- What do you do that gets you into trouble?

- Are there any major themes in your life which seem to repeat themselves perhaps in different contexts?

- Do you care more about yourself than others?

- If you obtained a livable pension today, would you still like to keep your job?

- What did you do when your father was angry at you? Mother angry at you? Friends angry at you?

- What does your spouse think of you? What do your children think of you?

- What do you do when your superior is angry with you? Coworkers angry with you?

- What do you typically do when under attack or faced with conflict?

- What are your major disappointments in life?

- What are your major disappointments at work?

- Who is responsible for your major disappointments?

- What made you proudest as a child? As an adult?

- What is your favorite daydream? Do you see anything in it that might be making you a more or less effective manager?

What is your single major accomplishment?

Most of these questions tap the manager’s underlying personality dynamics. They are questions which we seldom think about. The answers to them differentiate ourselves sharply from others.

Your defence mechanisms

For a variety of reasons we sometimes are unconsciously not interested in making a sound situational diagnosis. It may be that if we made a realistic diagnosis, we would discover things we do not like, or things we simply do not want to know, or things we do not know how to handle. The main, unconscious mental protective devices we use are known as defence mechanisms originally proposed by Sigmund Freud.

Defence mechanisms are not necessarily psychologically unhealthy. All healthy personalities need temporary protection from time to time. The problem occurs when the temporary protection turns into a permanent drop in situational sensitivity and so to a distortion of reality. The defence mechanisms operate entirely outside the awareness of some managers, operating in the unconscious, serving to hide or to shield them from what is unacceptable, threatening or repugnant in the situation so that these things become unrecognised or unacknowledged. In layman’s language, defence mechanisms give us blind spots we unconsciously think we need.

The main defence mechanisms managers should be aware of in themselves and others are rationalisation (inventing reasons) and projection (it’s you not me).

In addition to these two mechanisms, the following five factors also lead to low sensitivity: negative adaptation (accepting things as they are), symptoms for causes (mistaking appearance for cause), lack of conceptual language (not talking the same language), limiting value system (having one test for everything), and high levels of anxiety (being a worrier).

Rationalisation (inventing reasons)

Rationalistion involves inventing plausible but spurious explanations. For example, attributing the promotion of someone to office politics when in fact the promotion was based on managerial effectiveness.

Rationalisation involves inventing and accepting interpretations which an impartial analysis would not substantiate. It is kidding ourselves about what the world is really like. Rationalisation serves to conceal our view of the situation in such a way that the problem is seen as in the situation, not in ourselves. The justification of such interpretation usually involves giving socially acceptable reasons for behaviour or apparently logical reasons for the view of the situation. In business life, what is rationalised in this way is usually believed by the manager but is often not understood or believed by the listener.

All managers are familiar with rationalisation. They see it in the manager passed over for promotion who decided it was not wanted anyway. This is called ‘sour grapes’ (after the fable about the fox who could not get at some grapes and who then decided they were sour). Managers who continually ‘sour grape’ turn into one. Managers transferred against their wishes may later find that they like their new jobs. This is called ‘sweet lemon’ to suggest that we invest an unpleasant object or event with positive references when it is forced on us. It is clear that rationalisation at times is an excellent adaptive mechanism which enables us to meet negative circumstances. The change in opinion, of course, might be real and based on objective reality. In this case this is not rationalisation but a factual reappraisal.

Managers who are consistently late with their reports find many ways to rationalise their behaviour. They may blame subordinates, overwork, or unanticipated problems. For none of these delays, they feel, can they be held responsible. The real reasons may be fear of being evaluated by the report, unconsciously wanting to inconvenience report recipients, or simply incompetence. These real reasons are often not known to them. If they know them and still put excuses forward, they are not rationalising, they are lying.

Rationalisation is not rare. Some managers use it so much that it incapacitates them, most use it to some extent: “The job was not completed because other things came up”, “The promotion was missed because the superior was biased”, “The subordinates were fired because they were incompetent”.

Ordinary levels of rationalisation cannot be regarded as a serious problem but overuse can be. An incompetent manager, with a high need for achievement and an excessive fear of failure, might easily develop almost pathological rationalisations, perhaps leading to delusions of persecution. Managers might believe that their superior “Has it in for them”. This rationalisation may protect them from facing the real reasons for failure and lack of promotion. The overuse of rationalisation may so far remove managers from their real problems that they may end up with a crisis that cannot be solved. If we ‘save face’ too much, we may simply end up without a true identity.

Rationalisation is sometimes excusable on the grounds that it eases the shock of an unpleasant situation. It softens our misgivings about ourselves, eases our conscience, and enables us to restructure reality slowly so that it does not affront our view of ourselves. Some would say that if we did not rationalise we would go crazy. There is truth in this for less effective managers. For the effective manager, however, there is no substitute for reading a situation clearly, facing it squarely, and dealing with it realistically.

The problem with rationalisation is not so much that we fool ourselves but that it provides no guidelines for appropriate action. The essential ingredient of rationalisation is distortion to protect ourselves. This distorted perception leads to the identification of the wrong elements to change. Typically, managers who are rationalising may want to change others, or perhaps the technology, when they really should change themselves.

College students who do not participate enough in case study classes, where high student participation is expected, usually have a set of rationalisations to explain their less effective behaviour. These include: “Too many talk with nothing to say”, “Still water runs deep”, “We should have a public speaking course”, and even, “I was quiet when a child.”

The best tip of rationalisation in ourselves or others is the too perfect, too logical, or too consistent explanation. Life is fairly complex, and somewhat tentative explanations are what we usually must use. The rationalisation, however, is usually a logical masterpiece. All the bits fit together to make a perfect cover up story. Another tip off is the insistence with which the rationalisation is offered as an explanation. Shakespeare illuminated this with “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.” Winston Churchill was said to have sometimes written in the margin of his speeches “WPS”. It meant ‘Weak point –shout!’.

Projection (it’s you not me)

Projection is attributing to others what is in fact in one’s self. In short, “it’s them, not me.” It operates primarily in those with low style awareness, those who do not know how they, in fact, behave. The mechanism is most clearly seen in delusions of persecution. A new manager may be in the process of making changes in a department. Not all will like the changes, and each will react somewhat differently. Subordinates might feel aggressive toward this new manager but, because of social training, may not express it or even be aware of it. By the mechanism of projection, the subordinates then may suspect the managers of having these feelings and, as an extreme, believe themselves victims of a conspiracy.

Such statements as these may reveal projection at work: “The production department is not to be trusted”, “They are wolves in sheep’s clothing”, and “Every person has a price.”

Projection may be combined with rationalistion with undesirable results. Some managers cannot accept and do not see hostility in themselves. They may project this onto others and see the others as mean and aggressive. These managers then may have to rationalise why the other managers act this way towards them. One form is to develop a belief that others want the job or are trying to get them fired.

Typical examples of projection are the deserter who sees others as lazy, the selfish person who complains that others do not share and low relationships managers who are concerned that no one seems to take an interest in them.

A manager making changes in a department was mystified at the behaviour of two subordinates who resisted at every step, even to the extent of an unsuccessful attempt to get the manager fired. The two subordinates claimed that the manager was simply changing the department to suit the manager’s own ends. The manager was convinced otherwise and an objective external appraisal showed the changes were long overdue. The subordinates were almost certainly projecting their own feelings onto the manager. They wanted the old way as it suited their needs. But as this was unacceptable to admit to themselves, they convinced themselves that the changes were serving the manager’s needs.

Projection leads to low managerial effectiveness because it can only be maintained at the cost of continually misperceiving social reality. Although such distortion is designed unconsciously to protect the manager, the effect, in the long run, may be the opposite.

Negative adaptation (accepting things as they are)

One of the most important characteristics of human beings is their ability to make a psychological adaptation to an essentially unpleasant situation. Defence mechanisms help them do this. On the detrimental side, many managers adapt to negative conditions in such a way that they lose their sense of perspective about what an ideal situation might be. They believe that they, their department or the company, are operating reasonably well or even perfectly. An objective view would not confirm this. One particular advantage of using competent outsiders for advice is that they can see the true situation. They have had no opportunity to make a negative adaptation to the situation.

Negative adaptation is likely to be less common with those managers who have frequent contact outside the organisation, with those with much prior experience elsewhere or with those newly arrived. It can be reduced by a variety of training techniques designed to improve situational sensitivity and also by a sharper measure of managerial effectiveness.

Symptoms for causes (mistaking appearance for cause)

We are all ‘natural born’ psychologists and this leads us into many difficulties when diagnosing organisation events. Most managers, in fact, customarily make a psychological interpretation of events rather than a sociological one, even when the sociological one is correct. The ‘personality clash’ diagnosis for instance, in most cases is incorrect. The clash is often only a symptom and should not be diagnosed as a cause. To diagnose it correctly, it must be demonstrable that the managers involved will fight on the golf course or over a drink. If they are reasonably affable in these circumstance, it cannot be their personalities which clash. A more accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause might be ‘role conflict’. That is, their respective jobs are so designed that clashes are inevitable. As an example, suppose one manager was responsible for decreasing marketing costs and another for increasing sales; they did not report to the same manager and so had an ambiguous power relationship to each other. These managers, if committed to their jobs, would almost certainly fight. Is this best explained as personality conflict or role conflict? Clearly role conflict is the better explanation. The danger in calling it personality conflict is that both managers might be asked to take a human relations course and to be nicer to each other. Certainly this action would not get to the root of the problem, whereas a role-alignment meeting might.

Other such diagnoses which may be symptoms rather than causes are ‘communication problem’, ‘empire building’, and ‘apathy’. Like ‘personality clash’, these are not always best explained by saying “People are like that”.

Lack of conceptual language (not talking the same language)

Managers who talk and work together need a common set of concepts which they share and agree on. Without such a set, intelligent discussion is hindered. Disraeli spoke for many when he said, “If you want to converse with me, define your terms”.

One of the cornerstones of knowledge is the concept. A concept is simply a bundle of related ideas. To make talk more precise and economic we all use concepts. For example, we do not say that the car moved over a length 100 times 1,000 times one meter every 60 minutes. We, instead, make an equivalent but shorter statement and say that the car’s speed was 100 kilometers per hour. Without concept (in this example, speed, miles and hours) language would be clumsy.

So it is with management. Concepts make discussion more precise and often much briefer. Arguments are not, then, over definitions but over the realities of the situation itself. Without the concept of style resilience, it is difficult to quickly make the point that style rigidity has its good side. Without the concept of personal effectiveness, it is difficult to explain how someone can be more effective and yet less effective at the same time.

The 3-D terms provide a conceptual language to make discussion and analysis more precise. The concepts are the fewest possible needed to consider effectiveness, situations and styles. They are usable to improve situational sensitivity because they force a focus on elements, activities or outcomes that might otherwise be ignored or misinterpreted.

Limiting value system (having one test for everything)

Some managers have what amounts to an intellectual rigidity by espousing a single value or point of view which colours and sometimes covers reality. They may believe that all problems are human ones, that all work must always be satisfying or that bigness destroys initiative. Whatever the view, when deeply held, the managers are compelled to distort reality so that it fits their established point of view. This produces very simple explanations, since everything is explained in the same way.

With a similar kind of simplified approach, some attribute the same motive to whomever it is they disagree with. An example of a motive might be ‘power need’. But managers are not psychologists, and even psychologists do not agree upon which motives might be operating for a particular person in a particular situation. It is far safer and more accurate to observe and interpret behaviour, not motives, especially if we have a favorite motive we like to project onto other.

High levels of anxiety (being a worrier)

Some stage fright is usually a good thing. Moderate levels of anxiety tend to improve performance. Terror, on the other hand, usually does not.

As anxiety increases through low levels, performance also increases. There comes a point after stage fright level after which further increases in anxiety lead only to decreases in performance. Some persons are permanently anxious whatever the situation. They usually build up deep psychological defences to protect themselves from reality. Physical habits or strong ideological positions about what is right, are less likely to become distorted as a result of high levels of anxiety. Perception, interpretation of motives and feelings about others are likely to become distorted however. Situational sensitivity in particular can be sharply reduced as anxiety increases. But this is precisely the time when it is needed most. Managers at these times are wise to turn to less anxious associates in order to read the situation; and this is what they usually do. Sometimes it is their spouse. Too infrequently it is their older children.

Learning from feedback

One way to improve your situational sensitivity is to learn from feedback you receive. It might be from a candid subordinate or colleague. Managers who want to be more effective seek feedback actively. They are not so concerned with the somewhat trite distinction of feedback into constructive and destructive categories. They are concerned whether it is valid and as quick as possible. They become very interested if the feedback they receive is different from their perceptions. Something must be going on; “Here is my chance to learn.”

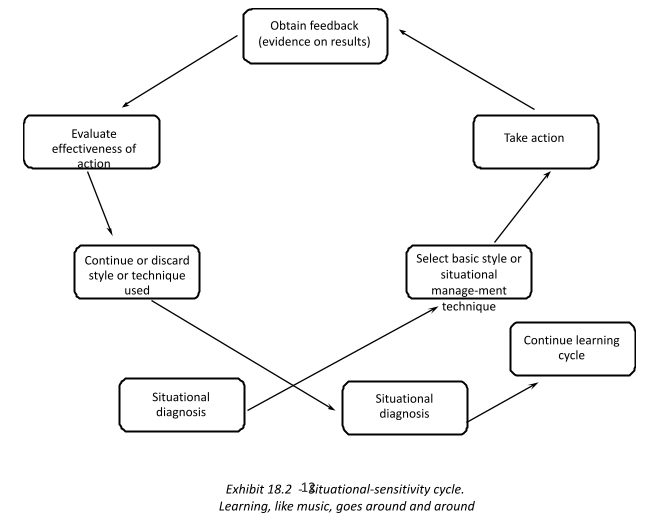

The feedback-learning cycle

Learning from feedback can be seen as a cycle continuously repeating itself. So long as the cycle is maintained, learning can continue. The two key elements in the cycle are making a sound situational diagnosis and obtaining feedback on the results of the actions.

The situational-sensitivity cycle of Exhibit 18.2 has six steps. The sixth step leads into a repetition of the cycle.

- A situational diagnosis is made.

- The manager decides to adapt to the situation or to change it.

- The manager takes action.

- The manager obtains feedback on the results of the action. Without this step, the feedback-learning cycle cannot continue. It is its weakest link since it depends on the climate the manager has created and the skill in listening and observing.

- The manager evaluates the effectiveness of the action, then decides whether it led to more or less effectiveness and how much more effectiveness is possible.

- The action taken is continued or discarded.

Learning is a continuous process. It is difficult to suggest where it starts or ends. An effective manager is constantly making a diagnosis of the situation, using style flexibility or situational management, and assessing the effectiveness of such actions so that the nature of these interventions can be improved upon.

How to analyse a situation

When you look at any situation you bring your knowledge and experience and perceptive skills to bear. On balance, this is probably the best way and the way you will continue to do so. However, somewhat more formal way has been developed that you may find of some use. It certainly will help you think of one or more things that you might otherwise overlook. Most situations requiring analysis involve some kind of change and change forces and this approach is based upon this idea. In chapter 20 on situational management many ideas will be given about how to introduce change, that is situational management. Here we are thinking of how to analyse the situation that may need change, situational sensitivity.

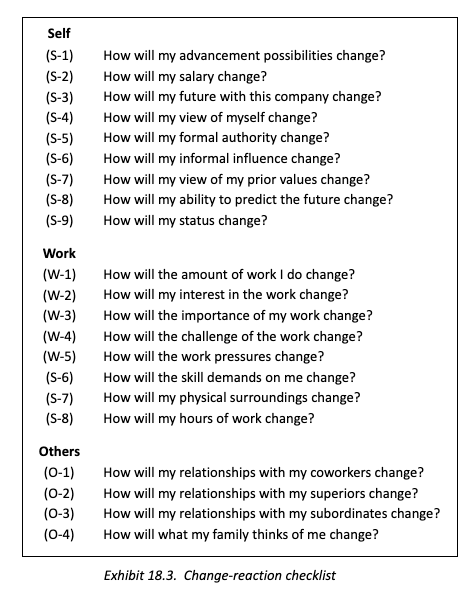

Reaction to change

The following questions summarise the majority of the ways in which change may be seen as affecting an individual. They are useful in getting a sharper focus on one or several underlying causes of the resistance. Use this list by considering each question in turn as if you were facing a proposed change. Check each question that seems important in increasing either resistance to or acceptance of, the change. Then put (+), (-), or (?) against each of those checked to indicate whether that particular factor is likely to increase acceptance, increase resistance, or whether the direction of influence is in doubt. If done well, this analysis provides an assessment of the situation as seen by those affected by the change. It can give leads to the existing restraining forces to be overcome or the main perceived benefits that might be enhanced further.

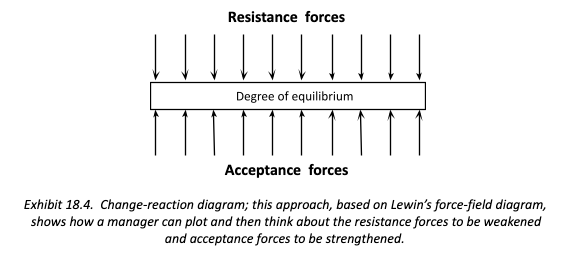

Change-reaction diagram

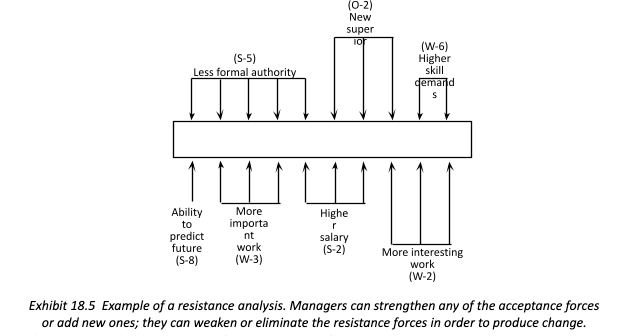

The change-reaction diagram is used to record the information from the change-reaction checklist. The basic idea of this diagram was proposed by the distinguished psychologist Kurt Lewin. It is useful as a guide for selecting a situational management strategy.

There are two basic strategies which may be used to facilitate change: an attempt to increase the acceptance of change or an attempt to decrease the resistance to change. These two sets of forces may be depicted as shown in Exhibit 18.4.

The 10 arrows pointing downward represent each of the resistance forces, and the 10 arrows pointing upward represent each of the acceptance forces. The number of arrows assigned to each force signifies the strength of the force. The total strength is always 10. The length of an arrow can represent how easily the force may be modified by situational management; so, the longer the arrow, the easier the underlying force is to grasp and modify.

The information obtained from the change-reaction checklist can be put on to the diagram by drawing in arrows and labeling them appropriately.

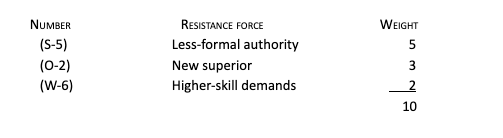

In this example three resistance forces are identified with the weights indicated:

The (O-2), new superior, force is drawn with longer arrows since many techniques can be used to decrease the feelings that usually surround the introduction of a new superior. Among the techniques are provision of background information on them, their early request for ideas to improve departmental effectiveness, a transitional period of a few days where old and new superior work together, and many others.

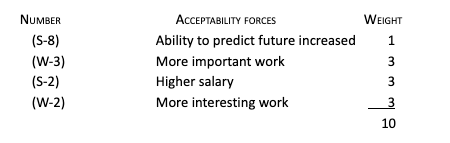

The acceptance forces are:

The (W-2), more interesting work, force is drawn longer because many techniques can be used to increase the interest of work. These are primarily of the job-enrichment type.

This kind of analysis is useful because it takes a rigorous approach to what is so often done very casually. It is always best to make such an analysis with at least one other person in order to increase the accuracy of the diagnosis.

As situations may be changed by weakening the resistance forces or strengthening the acceptance forces, each force identified should be so considered in this light.

The two remaining skills

This chapter was all about your situational sensitivity. Perhaps you have decided it is pretty high or perhaps you have decided it is not as high as you would like. We now move on to the two things you can do with your current level of situational sensitivity. You only have two options. You either change yourself: style flexibility, or you change the situation: situational management.

Taken from the book: “How to make your management style more effective”,

by W. J. Reddin, Section D, Chapter 18.

Published by Malaysian Institute of Management, Malaysia, 1990; pp. 151-165.